Posted on

Using data to catalyze and sustain cycles of continuous improvement in teacher preparation

Categories: Data, Lessons from the Field

Data, when interpreted in context and used appropriately, is a powerful tool for surfacing important trends and issues in education. For example, recent NAEP trend assessments reveal not only the consequences of pandemic-related disruptions on student learning, but also the varying results of education policies, remedial programs, and instructional priorities across state lines to address challenges. Additionally, shortages of qualified teachers are a growing concern across the country, yet when disaggregated, the data demonstrates that the issue is much more nuanced based on subject area, location, and how each state defines a qualified teacher.

But access to data doesn’t guarantee action based on that data. Regular, intentional effort is required to collect and analyze comprehensive data, identify root causes, and pursue solutions in order to drive effective, sustainable change.

Over the last six years, Deans for Impact (DFI) facilitated this rigorous work through an unprecedented cross-institutional effort, the Common Indicators System (CIS) Network.

In partnership with 26 schools of education from diverse contexts around the country, we collectively gathered and analyzed data on common indicators in the preparation of teachers to inform cycles of continuous improvement.

Educator-preparation leaders “are committed to changing the status quo,” wrote Tracey Weinstein, DFI’s vice president of data and research, in an early reflection on the CIS Network. “But to fulfill this commitment, these leaders need access to data that helps them understand what’s working and what needs to improve – and they need to know how to translate that data into actionable insights for program improvement.”

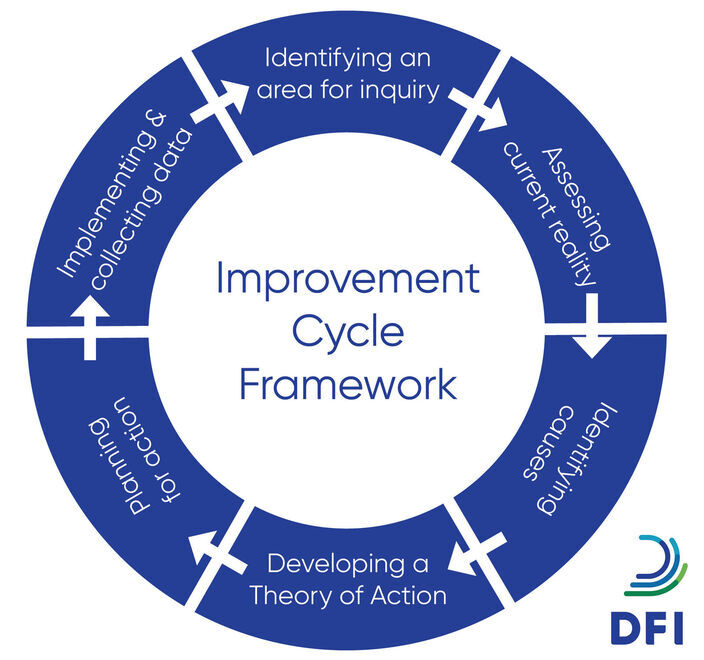

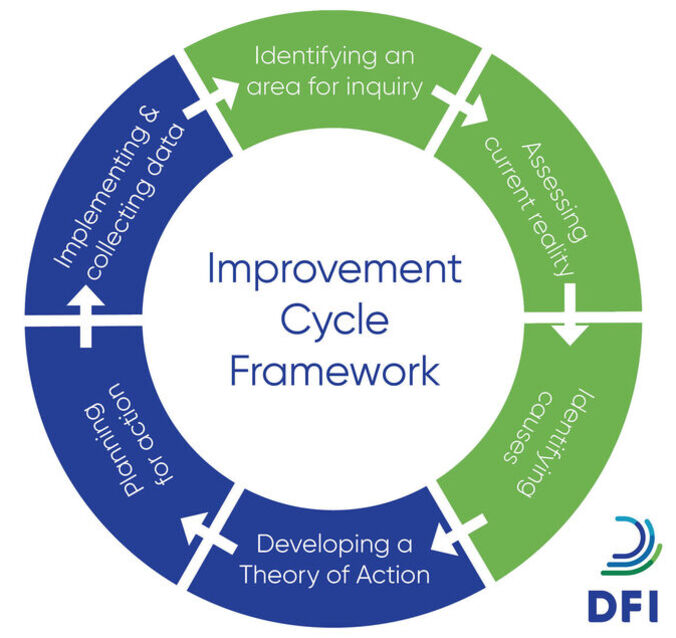

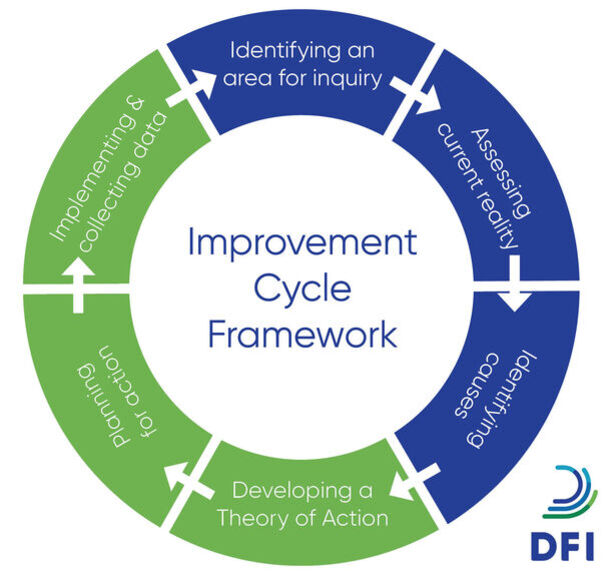

Throughout the years, participating program faculty and leaders have applied learnings from the CIS Network’s improvement cycle framework to not only strengthen how they prepare teachers in their own programs, but to also inform state-level data-driven improvement networks, revisit accreditation guidelines and processes, and share tools for using data effectively to drive improvement with state and district leaders.

Faculty at the University of Missouri-St. Louis – Senior Director of Clinical Experience and School Partnerships Stephanie Koscielski, Chair & Associate Professor April Regester, and Associate Chair & Assistant Teaching Professor Julie Smith Sodey – share reflections for how they leveraged learnings from the CIS Network about data usage for continuous improvement.

Identifying the challenge

Stephanie: When we joined the CIS network, we saw the Teaching Beliefs and Mindsets Survey (TBMS) as an opportunity for teacher-candidates to reflect on their teaching self-efficacy and beliefs, in the beginning and end of practicum (practice-based experiences), to see if there is a change over time. The network allowed us to then interpret our data in a number of ways – against our own certification areas, against the network data – to drill down on where we see areas for improvement.

April: It was hard at first. The TBMS language would say, for example, “greet students who are English Language Learners in their home language.” I found value in that but was doubtful about how it would tell me anything about our program. As we worked with DFI staff and other programs in our first year, we began to recognize that those specific measures were indicators of bigger ideas. We noticed that there were discrepancies between programs and what teacher-candidates were experiencing regarding coursework, early and mid-level field experiences, and practicums. We were able to review other evidence like community agency surveys and focus group data, data from our Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) Department of Education grant, Learning by Scientific Design (LbSD) items related to supporting equitable teaching practices, and specific course-embedded assessments. Being willing as an educator to learn about, understand, and communicate with students regardless of their home language, abilities, and cultural backgrounds revealed characteristics of a broader set of beliefs and mindsets held by our candidates.

The assessment results confirmed what we had been suspecting. Our elementary school teacher-candidates received content supporting diverse students and cultural-linguistic practices, but secondary students weren’t receiving those–and we saw the outcomes of that distinction reflected in their teaching self-efficacy results through the TBMS. To address this, we set out to improve how we prepare teacher-candidates to support emergent multilingual learners and their families across all programs.

Planning and pursuing solutions

Julie: We are fortunate to have a well-established, knowledgeable team of faculty and graduate students researching and teaching in TESOL. We partnered with them early in our CIS work and leaned heavily on their expertise to develop materials and strategies for helping more teacher-candidates develop skills and self-efficacy in working with emergent bilinguals and their families.

April: In implementing these changes, we started with professional development for instructors and faculty. We initially imagined that we’d train them, they’d adjust content in their courses, and materials and content we shared would get to candidates. But there were things that happened that we didn’t plan well for. There was a high turnover of instructors. We had invested an enormous amount of time and energy in professional development with instructors who didn’t end up teaching the following semester.

That required us to think deeper and differently. We needed to think about how to better use our time, and see more effective impact. Instead of our initial plan of filtering content down to teacher-candidates through instructors who didn’t end up staying, we increased our focus to be direct to teacher-candidates.

Julie: In another DFI network, Learning by Scientific Design, we had developed instructional modules that could be utilized in various course sections to help with natural attrition of part-time instructors and graduate teaching assistants. Through the use of well-scaffolded asynchronous instructional modules (curriculum that an instructor could take and assign “off the shelf” to ensure that all candidates have a similar experience of content), we were able to control the quality and consistency of key content. We applied this same practice to our work with our TESOL team to develop similar modules focused on teaching emergent bilinguals and connecting with their families.

April: We also pushed into other opportunities like grand seminars, which are all practicum-student professional development opportunities that take place five times a semester and operate like mini conferences for students.

In one of our CIS meetings around our plan of action for this, we were partnered with colleagues from Purdue and someone from their team asked us, “how have you been using peer-to-peer feedback among candidates?” We recognized that we could use grand seminar time more effectively and embed peer-to-peer feedback to allow candidates to learn from one another, especially from those who had placements with more opportunities to support emergent multilingual students and their families. It was a direct result from the opportunity of throwing ideas out into this network that were grappling with some of the same questions and goals, looking at it with fresh ideas, offering suggestions, and working closely with DFI staff as well to push our thinking further. It was a huge benefit of non-judgmental, non-competitive support around ideas to improve our specific goals.

Bringing diverse voices to the table

Stephanie: In one of our grand seminars, we brought candidates out of their regular peer groups and put them together with those from different certification programs to foster peer-to-peer discussion with prompts like: how are you communicating with emergent multilinguals? How is that different or similar? What ideas do we have to improve? Having them connect across programs pushed them out of their comfort zone and led to great conversations that generated a breadth of ideas. They were surfacing thoughts with one another and problem-solving together, outside of modules and other more structured opportunities to learn.

April: We wanted to make sure that the process and direction we were taking was effective and efficient for everyone. In teacher prep, we sometimes go through motions of what things typically have been done. Thinking outside the box allowed us to explore more effective ways to have sustainable impact and a holistic approach. The module development and grand seminars encouraged this for our candidates; we also consistently thought through what support also looked like for faculty and instructors, clinical educators, and people across the college as a whole, coming into the work from many different angles.

Julie: Sustainability is key in a teacher-preparation program like ours. As we have developed these important instructional shifts, a constant consideration is how to maintain and ensure these improvements over time.

April: Being able to implement changes, then regularly collect data to review the impact of those changes, was valuable. Our data became more consistent and clear. Over time, it became more predictable for us to identify what’s actually shifting in outcomes, and we could pinpoint various things to target that we felt had a bigger and broader impact related to students in the classroom. We have improved the experience for all of our candidates through this work, and their self-efficacy–as reported in the TBMS survey–has demonstrated this change. We can see what is working well, and as we continue to monitor our data we can make needed changes to improve our programs and student outcomes.

Interested in working with DFI to tackle unique challenges in your educator-preparation program or local context? Learn about our instructional support and get in touch.

Want to facilitate data-driven continuous improvement in your educator-preparation program? Download our resources: